Introduction: The Roadblock of Having Words but Not Communication

If you're a parent navigating the world of autism, you know that the word "communication" often carries the heaviest emotional weight. It's the key to connection, independence, and peace of mind.

Perhaps your child has words, but those words feel locked away. They might repeat movie scripts (echolalia) perfectly, or flawlessly name every dinosaur, yet they still struggle to simply ask for a snack or tell you they need a break. That's because speech is not the same as functional communication.

This struggle highlights a crucial distinction: your child doesn't just need vocabulary; they need to learn the power of language— how to use words to influence their world.

This is the exact problem the Verbal Behavior (VB) approach was designed to solve. As a powerful, evidence-based methodology within Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), the VB approach shifts the focus entirely from the structure of words (grammar, pronunciation) to their function (the reason we use them).

It's rooted in the pioneering work of psychologist B.F. Skinner, who taught us that every single utterance, sign, or picture exchange is a behavior driven by a specific purpose. It's the difference between knowing the word "milk" and using the word "milk" to actually get a glass of cold milk when you're thirsty.

In this article, we'll break down the components of VB in parent-friendly terms, showing you how this therapy teaches your child to use all forms of communication to genuinely connect and reduce their daily frustrations.

Section 1: What is Verbal Behavior Therapy (VBT) and Why Is It Different?

VBT: ABA Applied to Language, Functionally

The term verbal behavior therapy (VBT) is essentially ABA therapy applied specifically and systematically to teaching communication. The goal is simple, but profound: to develop language that is meaningful and social-language that serves a real-life purpose. It shifts the focus from passively naming items to actively using words to get things done.

The Critical Difference: Function Over Form

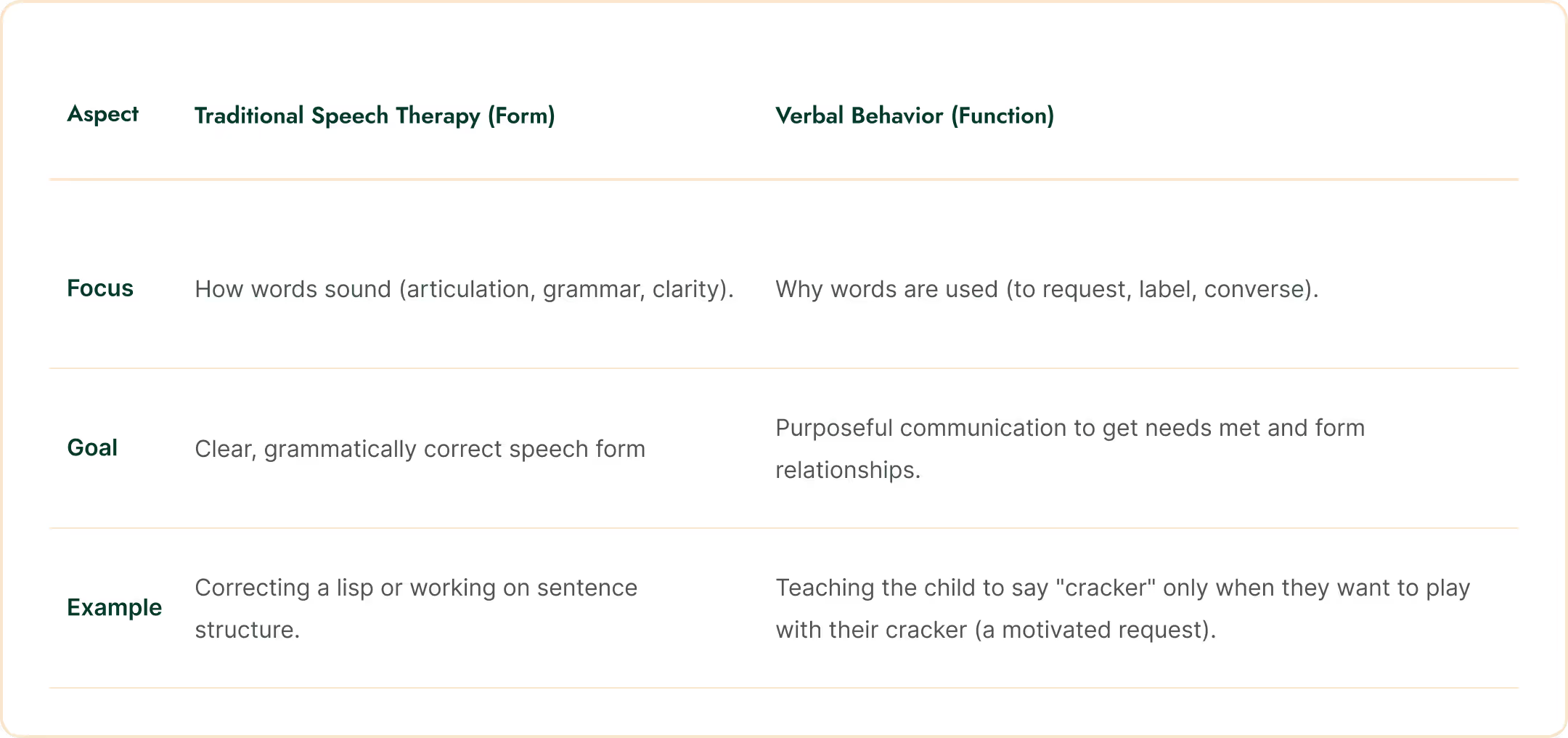

Many parents ask us, "How is this different from traditional speech therapy?" Both are vital and often work together, but their focus areas differ significantly:

In a quality VB program, a child saying "cracker" is reinforced entirely differently based on the underlying motivation. If the child is hungry and says "cracker," they get a cracker. If the therapist holds up a picture of a cracker and asks, "What is this?" and the child says "cracker," they get praise (not the snack). This relentless focus on the different functions is the essence of applied behavior analysis verbal behavior.

The "Verbal" Spectrum: Communication Beyond the Voice

Here is a common point of confusion: the word "verbal" does not just mean "vocal." In the world of VB, "verbal" simply means any form of communication that is mediated by another person. That means:

- Vocal (spoken words).

- Sign Language (manual communication).

- PECS (Picture Exchange Communication System).

- Typing/Writing (for older or advanced learners).

The therapist's priority is always to establish the fastest, most effective way for your child to begin communicating right now. If speech is slow to develop, they won't wait; they will immediately prioritize an AAC (augmentative and alternative communication) method like PECS or signing.

Section 2: The Core Functional Units-The Verbal Operants

The true magic of the verbal behavior approach is realizing that all communication-from a baby's cry to a complex philosophical argument-can be categorized into functional units, called verbal operants. These are the fundamental reasons why we use language.

Understanding these three main operants gives you the roadmap to your child's learning journey.

A. Mand (The Request: "I Want") - The Engine of Motivation

The Mand is the request. It is asking for something you want or need (an item, an activity, attention, or a break).

Definition: Asking for something driven by a current state of deprivation (a need or a want).

The Consequence Magic: The consequence is always, immediately, getting the item or activity requested.

FAQ Integration: Why are Mands taught first, and how do they reduce challenging behavior?

This is arguably the most critical piece of the puzzle. Mands are taught first because they are the only operant driven by pure, internal motivation.

Imagine your child is screaming and banging their head because they want the blue toy car on the shelf, but they can't ask for it. The tantrum is their communication. When we teach them to mand—to say, sign, or exchange the picture for "car"— and they immediately receive the car, two life-changing things happen:

- They gain control: They learn their voice (in whatever form) has power. This immediately reduces frustration because they now have a functional, appropriate tool to control their environment.

- They trust the therapist: The therapist becomes the person who delivers the "goods," strengthening the teaching relationship (often called "pairing").

A child who learns to mand effectively is a child who is ready and motivated to learn all other forms of language. It is the core function of communication that brings immediate relief and engagement.

B. Tact (The Label: "It Is") - Connecting Words to the World

The Tact is the label. It is naming or labeling something in the environment that you can see, hear, smell, or feel (objects, actions, emotions, etc.).

Definition: Naming something in the environment upon sensing it.

The Consequence: The consequence is social reinforcement—a high-five, enthusiastic praise like "You're right!", or maybe a token, but not the item itself.

The Crucial Distinction

If the child says "cookie" because the therapist asked, "What is this?" and they are only rewarded with praise, that's a Tact. The motivation isn't hunger; it's the social recognition of correctly identifying the object. If the child says "cookie" because they are hungry and they get to eat it, that's a Mand. Teaching the child the difference between these two contexts is vital for flexible language use.

C. Intraverbal (The Conversation: "Answering Questions") - The Bridge to Social Skills

The Intraverbal is the conversation. This is responding to another person's language when there is no picture or object present. It is recalling information from memory based purely on a verbal prompt.

Definition: Responding to verbal stimuli (a question, a fill-in-the-blank, or a greeting) with language.

Difficulty: This is usually the hardest operant to master. Why? Because it requires greater cognitive flexibility and relies purely on auditory input and memory. There's nothing to point to, nothing to hold, and no obvious visual cue.

Parent Example:

- Fill-in-the-blank: Therapist says, "Twinkle twinkle little..." Child says, "star."

- Recalling Facts: Therapist says, "What color is a banana?" Child says, "Yellow."

- Personal Information: Therapist says, "Where do you live?" Child says, "Denver."

Mastering the Intraverbal is the ultimate bridge to real social skills. It allows your child to answer questions, share memories, tell jokes, and participate in the fluid back-and-forth that defines friendship and family conversation. Without it, social interaction remains severely limited.

Section 3: The Foundational Building Blocks

Before a child can effectively Mand, Tact, or engage in conversation, they often need to master two critical foundational skills, sometimes called pre-requisite operants:

A. Echoic (Vocal Imitation: "Say What I Say")

If your child has vocal abilities, the Echoic skill is their warm-up. It is simply repeating a word or sound exactly after a model. It helps build a sound repertoire, which is essential for developing clear, functional speech. If a therapist wants to teach the Mand for "juice," they may first use an Echoic trial: "Say 'juice.'" The immediate consequence is praise, which makes the child more likely to attempt to imitate other sounds.

B. Listener Responding (Receptive Language)

This is what we traditionally call "receptive language" or "following directions." Listener Responding is the non-vocal response to language. It demonstrates a child's comprehension of language even if they cannot speak it themselves.

Function: Demonstrates understanding (e.g., Therapist says, "Touch your nose." Child touches their nose. Therapist says, "Stand up." Child stands up.)

This skill is often one of the first areas to show rapid progress and is crucial for safety and following classroom instructions.

Section 4: Implementation and Generalization: Making It Stick

How VB Looks in Practice: Structured vs. Natural

The principles of verbal aba are applied using a mix of teaching environments:

Structured Practice (DTT in VB): VB often uses Discrete Trial Training (DTT) techniques (fast-paced, rapid repetition) to quickly introduce and strengthen a new operant, such as Manding for three new toys.

Natural Practice (NET in VB): VB thrives in Natural Environment Teaching (NET). This is where the skill is truly cemented. Mands are taught when the child is naturally motivated (e.g., holding a favorite juice box just out of reach and prompting the Mand). Tacting is taught when a child is looking at an interesting bird outside the window. This makes the skill relevant and powerful, teaching them when and where to use their new language.

Generalization: The Real Goal

The whole point of the VB approach is not for your child to just speak well in the therapy room. The goal is generalization-using the skill:\

- With different people (Mom, Dad, teacher, grandma).

- In different settings (home, school, playground).

- With different materials (a real apple, a picture of an apple, a toy apple).

The therapist's job is to constantly mix and vary the operants to gain that cognitive flexibility. They might transition from a Mand for the apple, to a Tact of the color, to an Intraverbal of the song "A-P-P-L-E." This variation prevents the child from getting stuck in rote memorization and builds genuine, fluid conversational ability.

FAQ Integration: How do I carry over VB skills at home without being a "therapist"?

This is the question every parent asks! You are not expected to run formal DTT trials, but you can effortlessly reinforce the VB approach throughout your day:

- Set the Stage for Manding: Look for opportunities where your child needs something (a drink, a toy, a door opened) and use that moment as a brief teaching opportunity. Hold the item just out of reach and prompt the Mand ("What do you want?"). Immediately honor the request when the child attempts the communication.

- Narrate and Tact: When you are doing a fun activity (like going to the park or playing with blocks), narrate what you are seeing and prompt Tacting. "Look, a dog! What do you see?" or "That's a blue block. Can you put the blue block down?"

- Use Fill-in-the-Blanks: During reading time or singing familiar songs, pause deliberately for the child to fill in the final word (Intraverbal). This is the easiest, most natural way to build conversational recall.

Communication is Connection and Empowerment

The Verbal Behavior approach is far more than just teach words; it's a functional roadmap that teaches children the power of their language. Understand the core operants-how to Mand (request), Tact (label), and engage in Intraverbal (conversation) gives you a clear, functional view of your child's therapeutic journey.

The ultimate goal of this verbal aba is empowerment. It reduces frustration through replacement challenging behaviors with functional communication, and it builds the foundation for complex social interactions. When your child learns to communicate effectively, the world opens up, and meaningful connections become possible.

We strongly encourage you to partner closely with your child's supervising Behavior Analyst. Ask them how they are specifically categorize your child's current communication goals by operant (Mand, Tact, Intraverbal) to better track their progress toward fluency and independence.